Back when energy was a lot more expensive than it is today (and who knows how long that will last), we opted to use our wood stove for heat every day instead of just occasionally. This strategy requires a lot of work, more so for our being at such a high latitude. With long winters and short summers, there is only a short time to dry wood and a long time during which you need it.

It’s mostly enjoyable work, and we’ve developed ways to spread it out a bit so it doesn’t become too onerous. One way we spread it out is that I split wood all winter, just keeping a little ahead of what we need to burn. It’s therapeutic. Getting really dry wood has been a challenge, though. Unless you cut and split in late winter or early spring, chances are good that your wood won’t be dry by the next winter. This is especially true if we get a wet August and September, which happens some years. We went with the two-summer (or more) option, cutting wood that we wouldn’t burn for two years. Once you have that buffer, it’s much easier to have dry wood on hand. Until you get a really wet summer, then even tarps over the drying wood stacks may not be enough.

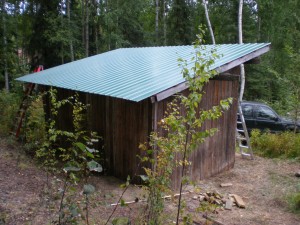

We juggled methods for several years before I finally decided that we’d be better off with a wood shed. The folks who’d built our house back in the 1980s had at some point owned horses and had built a small horse shed for these animals in the woods below the house. It was basically useless to us, being too far from the house. We did as they’d done in later years and just stored low-priority things in there. If it was closer to the house, it would make a good wood shed. So I decided to move it.

Once I’d decided where the shed could be put, I numbered all the boards with pencil on the inside and took it apart. It had been made with nice, rough-sawn, full-dimension spruce from this area. I was able to count rings on a couple of the 2 x 6 boards and found them to be from trees that were 80-100 years old. The shed had been put into the woods in such a way that it was not possible to get a truck up next to it, so I did all the hauling by hand. Every day I’d haul ten loads up the hill and pile it next to the new site.

When it was all apart and moved, I dug holes to plant the structural posts. They had been made of treated timber and were still in perfect condition, so in they went. Once they’d been squared with each other and leveled, I tamped them in and began putting the whole thing back together. This is where the numbered boards helped a lot. It all went quite smoothly, except for the roof. Originally, it had been built with translucent plastic roofing, which had kept the interior light in the summer. This had deteriorated, as had the boards to which it was attached. So I had to replace those, and for the roof itself I used metal instead. It turned out well.

Once we had a real wood shed, we stocked it with wood that we’d let dry in there for over a year to burn during the next winter. I can report that that’s working out beautifully. The wood is so dry that we’re able to start fires in the wood stove with ease, needing remarkably little kindling. During the winter I am out there every day, reloading wood carriers for inside and, on at least two days a week, splitting more wood. So overall it’s a successful experiment and a great change from the past.

“I saw something nasty in the woodshed.” -Cold Comfort Farm

I had forgotten that. We don’t get many nasties in our woodshed. Once I found a dead robin high on a shelf that looked like it had been dragged in and eaten by a squirrel. And a vole got trapped in the kindling bucket one night (it couldn’t get up the side to get back out), but I let it go, so it had a happy ending.